Life in the South was certainly complicated for women left on the home front during the Civil War. Besides the obvious dangers of living without the protection of their menfolk, Southern women were compelled to carry on work on farms and in factories for much need food and supplies for their own families and as well as the armies. There are many family histories that tell of the heroics of Pickens County women during these times — tales like a “frail” wispy granny blasting the rump of a smokehouse thief with buckshot! A war time newspaper correspondent from Alabama reported, “the most novel think I have seen in some time was a woman plowing yesterday with a pistol buckled around her”, and her child sitting in the field some distance away.

There was yet another call to the women in the North Georgia area — a noble call to render assistance to soldiers of the Confederacy. And their answer to this call would be a effort for which they were only quietly lauded. The story unfolds this way …

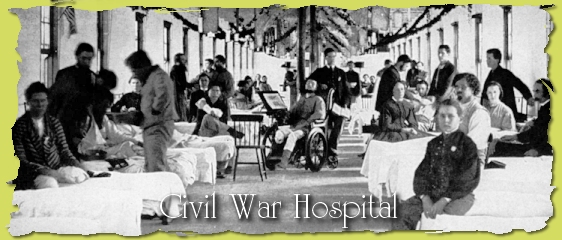

In November 1862, Confederate military authorities toured the city of Rome in Floyd County to determine its suitability as a site for army hospitals. Finding it favorible, the conversion of Rome into a convalescent center was swift. By December of that year, a number of Rome businesses had been shifted from their premises to make room for the new facilites. At some point during this transition, a newspaper “in the North” printed an article that raised the ire of women in the South. On April 19, 1863, the Tri-Weekly Courier newspaper in Rome published a letter signed “Mary” asking that a Ladies Hospital Association be organized to refute “recently circulated slurs” against Rome’s womanhood for not having come more readily to the aid of the city’s hospitalized soldiers.

As a result of this plea, the Ladies’ Hospital Relief Association was formed on April 25. Other groups formed at varying times during this plight were called the Ladies’ Aid Society and the Soldiers’ Aid Association. These little societies were diligently organized, adopting constitutions and by-laws, and charging $1 a year membership dues.

Women of these groups canvassed the area for members and supplies. Much of their time was spent cutting bandages out of old sheets and the like, and in combing old table cloths for lint to be used in the healing efforts.

An account of their charitable acts tells of “beautiful tableaux” being set up at City Hall in Rome by the Ladies’ Aid Society, the viewing of which brought contributions of $137.70 to The Cause. One scene in the tableau was described as ‘the state of Kentucky in chains held by President Lincoln’, and other scene was the ‘state of Maryland prostrate and Lincoln bending over her with a sword’. (Editor’s comment It would certainly appear that the political environment of our country today could lend itself to some rather interesting tableaux, perhaps to help the MVHS raise money for special projects?!) In January 1864, the fight grew closer to Rome, and the town was booming. Women and children from the surrounding countryside crowded into whatever living space was available in the town for protection, both from the approaching Union forces and the sometimes marauding local militia. More and more of the town’s established businesses were required to vacate their buildings to hospital growth, but even more newer businesses sprang up in new locations to serve the ever-growing populus of evacuees and soldiers. The peak of this activity came on May 17. On that morning, it is reported that Confederate troops left the city as they “enemy” approached — and on that evening, the city was occupied by the first Federal troops.

The hospitals in Rome had been making a surrepticious retreat of their facilities southward since January. The increasingly severe shortage of provisions played a big part in this relocation, as was the absence of enough medical personnel. When the occupation of the city by the Federal army was complete, many downtown buildings formerly used as Confederate hospitals were commandeered by Union medical officers. Even those facilities proved inadequate for the treatment of vast numbers of Federal casualties shipped into Rome during what was to be the final stages of the War.

During this period of great suffering and chaos in North Georgia, a this quote from a letter written by Mr. William Howe in Rome seems a fitting tribute to the efforts of these volunteer nurses: “God bless our women! Here their trud worth is felt. Every comfort, every appliance to the wants of the sick is within my reach; and when I have occasion for a clean pillow slip, sheet or towel, the closet is crammed full of them, and I involuntarily explaim, ‘God bless them’!”

This story came to light when the writer was researching the history of several Pickens County families and noted that more than one young mother had given birth in Rome in late 1863 and early 1864. This seemingly unusual occurrence has been explained with the discovery that they had fled Jasper with other relatives during a panic of approaching Federal soldiers, and were subsequently engaged as volunteer nurses in Rome’s vast hospital complexes.

by Sylvia Caldwell Rankin

Originally published: Marble Valley Historical Society newsletter/May 1998